High Prices for Essential Drugs: A Risk for Public Health, Catastrophic Health Spending, High-Debt Levels, and Impoverishment

As all of us who have been sick or diagnosed with a chronic condition that requires adherence to a daily drug regime know, timely access to required medicines not only helps us get better or manage a health condition over the long term, but saves us from hospitalization if the disease is not controlled, helps us avoid being absent from work, improves our productivity, and enhances our quality of life.

So, from an ethical, societal, and public health point of view, it should not be accepted that the sick or those living with a chronic condition are put at risk of ill health, premature mortality and disability, catastrophic health spending, debt and impoverishment because they cannot afford essential medicines when needed, or are forced by high drug prices to ration their medication, aggravating their health condition and even putting them at risk of death.

Although this dire reality is common in many countries of the world, the current political debate in the United States is illustrative of this global public health challenge as high drug prices are a top concern for families across the country, who face common threats often found under private health insurance arrangements: pre-existing clauses that do not cover a medical condition that started before a person's health insurance benefits went into effect, as well as high deductibles, co-payments, and lifetime limitations in services and drug coverage.

The high cost of insulin, a lifesaving medication needed to manage Type-1 diabetes, which affects about 5 percent of people with diabetes in the United States, is a good example of the ironies, inequities, and negative social impact of the lack of or limited access to essential drugs in the country. Indeed, it is not only ironic but I would say it is morally wrong that drug companies have been profiting from selling insulin at high prices, in spite of the fact that Frederick Banting and John Macleod, who were awarded the 1923 Nobel Prize in Medicine for its discovery, sold the patent to the University of Toronto for $1 each because they felt that insulin belonged to the world and not for their enrichment.

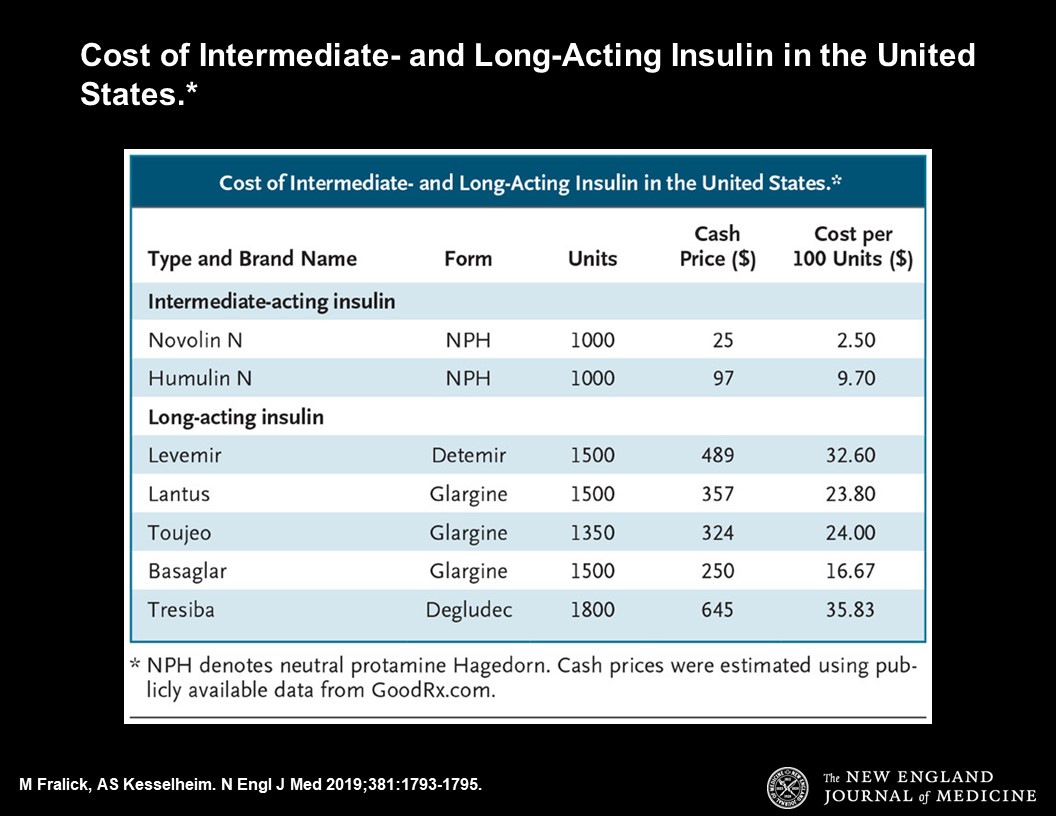

As described by Michael Fralick and Aaron S. Kesselheim, in a recent article in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), almost 100 years after its discovery, insulin is inaccessible to thousands of Americans because of its high cost. The information presented in the article shows that the price of insulin in the United States has risen substantially over the past two decades: “today, the price of 100 units of short-acting insulin for adults without insurance is about $18. The usual dose for regular insulin is 0.5 to 1.0 units per kilogram per day (usually given before meals). Thus, for a person with type 1 diabetes who weighs 70 kg and is taking a dose of 1 unit per kilogram per day, 100 units will last less than 2 days. Most adults taking short-acting insulin also require either intermediate- or long-acting insulin, the latter of which is also quite costly” (see below table from the NEJM article).

The difference in drug prices between the United States and the rest of the world, is mindboggling. In some cases, as with the fast-acting insulin Novolog, it is 74% cheaper when ordered from a pharmacy in Canada. In should not surprise us, then, that while the United States represents only 15% of the global insulin market, it generates almost half of the pharmaceutical industry’s insulin revenue.

What can be done to deal with the rising cost of insulin and other prescription drugs in the United States and elsewhere? How can essential drugs become more accessible and affordable?

While the mandatory provision of an essential outpatient drug benefit package for priority, high-burden diseases, such as Type 1 diabetes, under publicly-funded arrangements or health insurance plans is a critical measure to guarantee their timely access and affordability, additional measures as those now being debated in the United States are needed, including supply side measures such as price negotiation, changes in patent laws, and the manufacture of generics.

An essential drug benefit program, that eliminates or caps-out out-of-pocket drug spending for everyone, could be funded through an improved allocation of overall public expenditures, including a shift toward long-term social needs such as health and away from less productive categories of public expenditures (for example, untargeted subsidies and transfers, general administration expenditures and unproductive public investments). Other funding options include, as already done in some countries, increasing taxes on cigarettes, alcohol, and sugar sweetened drinks, since current tax rates are evidently far below what is feasible in terms of revenue potential and the generation of health benefits.

If we focus on insulin as a tracer of the problem, then the need for supply side measures becomes clearer. As explained in Fralick and Kesselheim’s article, the rising cost of insulin in the United States can be attributed primarily to two phenomena: first, the current law allows pharmaceutical manufacturers to price their products at whatever level they believe the market will bear and to raise prices over time without limit (this practice is the opposite of what England does, where the government sets a maximum price it will pay for a drug when directly negotiating with the pharmaceutical industry); and second, direct competition in the insulin market is lacking (approximately 90% of insulin sold in the United States is manufactured by one of three companies: Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi).

The plan proposed by Michael Bloomberg, the former Mayor of New York and Global Philanthropist, to lower the prices for essential medications for everyone in the United States, offers a good road map that merits consideration. It calls for the adoption of legal measures and requirements that authorize governments and insurance companies to negotiate drug prices with the pharmaceutical industry in order to lower prices for everyone; it promotes the selection of most cost-effective drugs, including generics; it allows for the importation of safe drugs from other countries with good quality standards and where prices are lower; and it changes patents and intellectual property laws to foster competition by bringing generic drugs to the market faster (in the United States, brand-name drugs account for 72% of total drug spending despite representing only 10% of all prescriptions) to reduce drug costs.

While timely access to medications such as insulin is critical to manage Type-1 diabetes, the promotion of health literacy (the capacity of individuals to obtain, communicate, process, and understand basic health information and services to make appropriate health decisions), is equally vital for the development of a disciplined daily nutritional regime, rich in proteins and vegetables, with reduced or no carbohydrates from processed foods, and physical activity, to manage this disease.

In pursuing universal health coverage, therefore, we need to remember that besides putting in place arrangements that ensure access to medical care and offer financial protection to the population, investment in health literacy can empower people to be in the “driver’s seat” of health promotion and disease prevention, including the prevention of complications from existing chronic health conditions such as Type-1 diabetes, to lead healthy, productive and happy lives.