Safe Water, Basic Sanitation and Hygiene: An Essential Investment for Health

Today, World Water Day 2022, is an opportune time to have a look at the societal risks of contaminated drinking water. Indeed, a lack of access to safe water is considered one of the top health risks based on impact to populations.

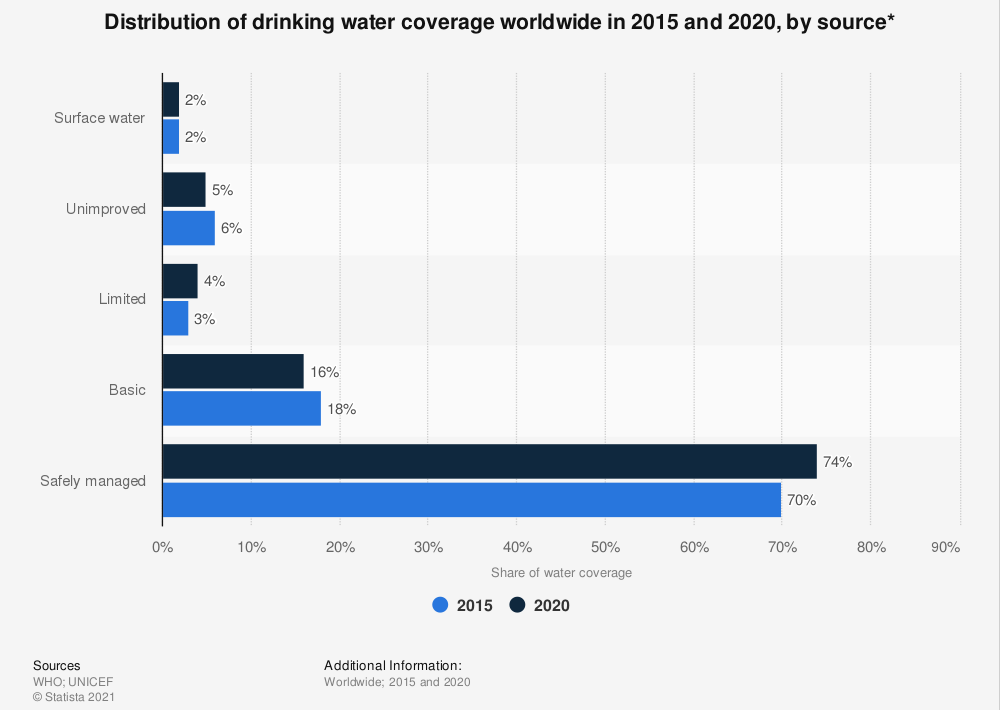

Overall, as shown in Figure 1, by 2020, an estimated 90 percent of the world population had access to at least basic drinking water services, defined as access to protected wells or springs in less than 30 minutes distance. Yet, several countries, especially in Africa, still have a way to go to provide their citizens with safe drinking water. About 772 million people around the world still lack even basic access to basic drinking water services.

Figure 1:

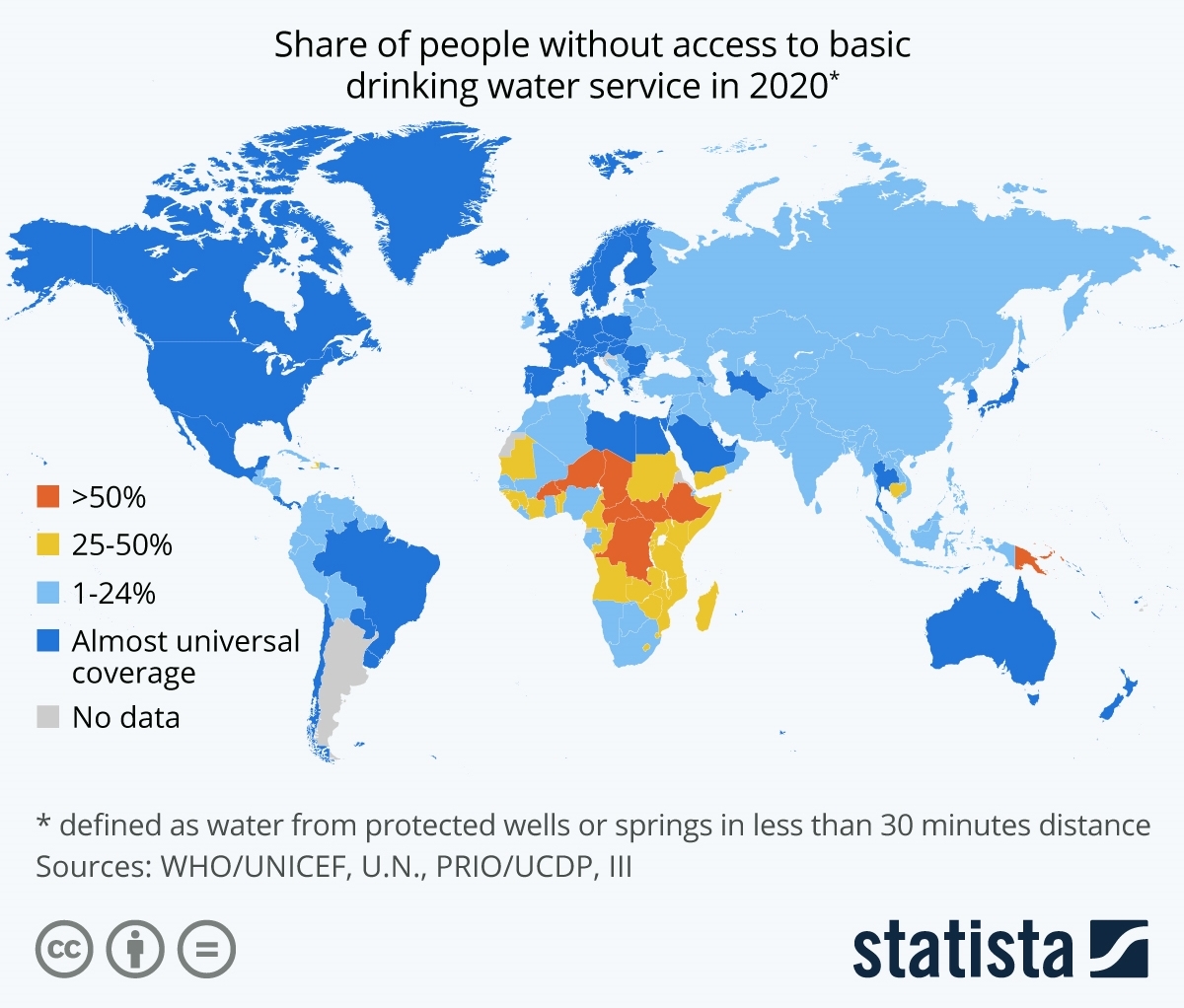

Figure 2 shows the share of people without access to basic drinking water service in 2020. The map highlights the big disparities between regions and countries, and within countries. While access was highest in Europe and North America and Australia and New Zealand, with 100 percent of both regions having access to at least basic drinking water services, just 65 percent of the population in sub-Saharan Africa and 59 percent of the population in Oceania had basic access. In sub-Saharan Africa, about 16 percent of people had access to unimproved water sources and eight percent only had access to surface waters. Unimproved water sources include bottled water and tanker-trucks. Currently, eight out of ten people living in rural areas still lack even basic drinking water services.

Figure 2:

Water is one of life’s essential needs but water inequality is a major issue worldwide. The varying access to safe water worldwide also creates considerable gaps in access to basic sanitation and hygiene services (e.g., handwashing, food hygiene). Nine percent of the global population had no access to basic handwashing facilities at home in 2020, and it is estimated that there are 2.4 billion people living without access to improved sanitation facilities. Again, the largest proportion of the population affected by these conditions is in sub-Saharan Africa. For example, more than half the populations of many countries in Africa have no handwashing facilities at all. The risk of droughts, likely to be exacerbated in the future by climate change, growing populations and demand for water services, and increased water withdrawals, are expected to increase water scarcity.

Should this situation be of concern and matter to public health workers like me who work with health systems, who are not sanitary engineers?

The answer is a definite yes, since improving safe water and basic sanitation systems is a necessary complement to primary health care services and targeted nutrition interventions for reducing deaths and ill health in rural and urban slums where the poor concentrate. Unsafe drinking water, inadequate availability of water for hygiene, and lack of access to sanitation together contribute to about 88 percent of deaths from diarrheal diseases, or more than 1.5 million of the 1.9 million children under age 5 who perish from diarrhea each year. This amounts to close to 20 percent of all under-5 deaths and means that more than 5,000 children are dying every day as a result of diarrheal diseases. Cholera, an acute diarrheal disease linked to contaminated water that can kill within hours if left untreated, infects up to 4 million people each year, and kills an estimated 21,000-143,000 people.

The spread of other diseases, like typhoid and measles, increase precipitously in low-and middle-income countries when domestic water supply outages occur. In some individuals these diseases are fatal, and in many others their burden leads to reduced labor productivity and wages. Where the burden is high, repeated illnesses for family members can trap households in a vicious poverty cycle.

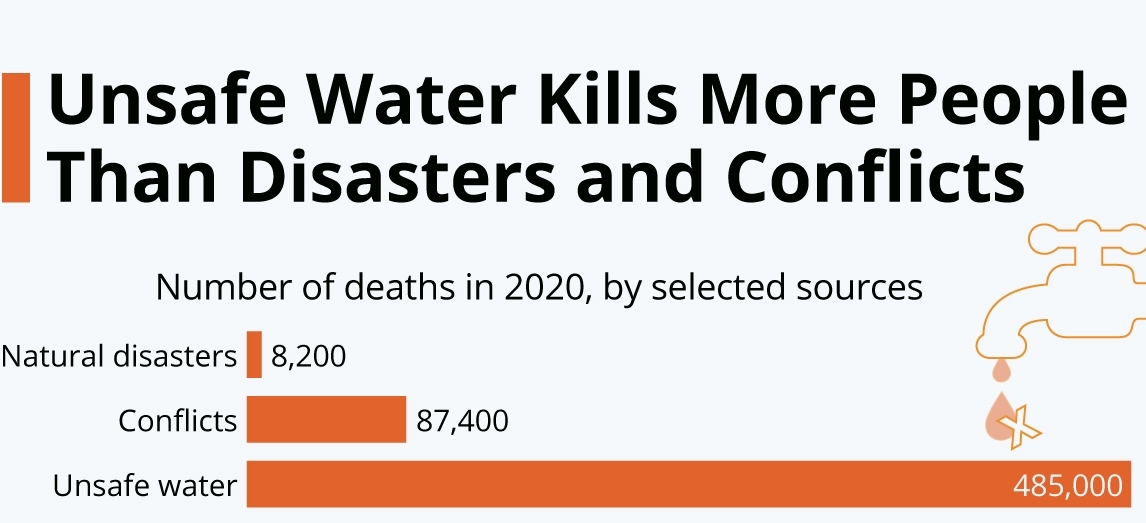

Overall, as shown in Figure 3, unsafe water kills more people than disasters and conflicts combined.

Figure 3:

Source: Adapted from Statista 2021.

The negative societal impact of the gaps in access to safe water, basic sanitation and hygiene services (WASH) are aggravated by the lack of these services in health care facilities (HCFs), posing health risks to patients, health workers, and other staff to develop HCFs-acquired infections. Indeed, a recent global report highlighted that one in four HCFs lacks basic water service (affecting more than 900 million people), one in five HCFs has no sanitation service (affecting about 1.5 billion people), and one in six HCFs has no hygiene service.

What to do?

The dilemma for the international community is simple: Are we going to wait to treat sick children and adults in newly renovated health clinics offering drug therapy and keeping them in costly hospital beds, or should we channel scare resources to building sustainable WASH services (safe water and basic sanitation systems, complemented with good hygiene practices), that prevent people from getting sick in the first place?

Safely managed WASH services are an essential part of preventing and protecting human health in normal times, during infectious disease outbreaks, including the current COVID-19 pandemic, and for the recovery phase of a disease outbreak (e.g., improved capacity of schools, workplaces and other public spaces to maintain effective hygiene protocols when they re-open).

Many co-benefits will be realized by safely managing WASH services and applying good hygiene practices. Improving sanitation management, for example, can have a profound impact on drinking-water quality from both surface and vulnerable groundwater sources, particularly when sewage or excreta contaminate drinking-water sources. If not managed well, secondary impacts can increase the risk of further spreading water borne diseases, including potential disease outbreaks such as cholera, particularly where the disease is endemic.

Hence, it should be clear that WASH services are needed to support affected, at-risk, and low-capacity countries to build resilience against future pandemics, as well as against diseases that afflict the poor in the developing world on a more routine basis. Basic WASH services and medical waste management in health care facilities are also essential for the delivery of safe and quality health care.

Takeaway

Working in rural areas high in the Andes of my native Ecuador a couple decades ago, I saw how improved access to safe water and basic sanitation, and good hygiene practices, could significantly reduce diarrhea-related morbidity combined with hygiene awareness and the use of latrines, safe disposal of feces, and hand washing. And regular vaccines and basic health checkups and proper nutrition, particularly to deal with children’s Iron, Iodine, and Vitamin A deficiencies, help eliminate much of the infectious diseases burden.

While we should rejoice about the progress achieved over the past decade to improve the access to WASH services worldwide, we also should heed the example of John Snow, one of the pillars of modern public health, who in the mid-1800s successfully demonstrated that the removal of pumps that supplied contaminated water controlled the cholera epidemics that were common in London at the time. By applying our public health knowledge about how infectious diseases are diffused and spread within communities, we could make a major and lasting impact by working together with our water and sanitation colleagues to tackle the source of these diseases, rather than just their symptoms.